The night caught them half a mile from camp

The rest of the day passed in talking and walking. The travellers, chatting and admiring the scene, followed the banks of the Wimmera. The cranes and the ibises took flight at their approach, uttering hoarse cries. The satin bowerbirds hid among the upper branches of the wild figs trees. The orioles, wheatears, epimachus, and many others flitted about among the branches of the liliaceous trees. The kingfishers abandoned their usual fishing, but the civilized family of parrots: the blue mountain, clothed in the seven colours of the prism; the little rosella, with its scarlet head and yellow throat; and the red and blue lory persisted in their deafening gossip at the top of the blooming gum trees.

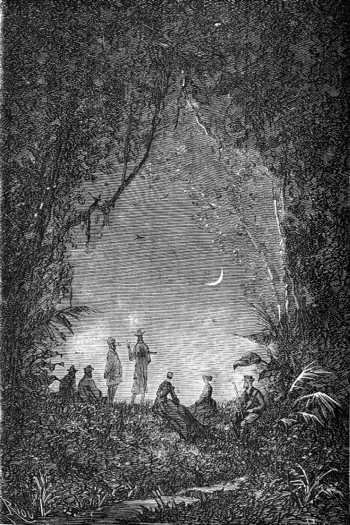

The night caught them half a mile from camp

The travellers admired this beautiful nature until sunset, sometimes resting on the grass beside the murmuring waters, sometimes wandering between groves of mimosas. At length the night, preceded by a momentary twilight, caught them about half a mile from camp. They returned, guiding themselves not by the pole-star, which is invisible in the southern hemisphere, but by the Southern Cross, which glittered in the sky half way between the horizon and the zenith.

Mr. Olbinett had laid supper in the tent, and they sat down to eat. The masterpiece of the banquet was a salmis of parrots, which Wilson had dextrously shot, and the steward had skilfully prepared.

Supper over, they only needed the slightest excuse to justify not going immediately to sleep on so lovely an evening. Lady Helena pleased everyone when she requested that Paganel relate the adventures of some of the great Australian explorers, a story which he had long promised.

Paganel wished for nothing better. His listeners stretched out at the foot of a magnificent banksia; the smoke of cigars soon rose to the foliage lost in the darkness, and the geographer, drawing on his inexhaustible memory, took the stage.

“You remember, my friends, and the Major will not have forgotten, the enumeration of the explorers which I made to you on board the Duncan. Of the many who have sought to penetrate to the heart of the continent, only four have succeeded in crossing it from south to north or from north to south. These four were Burke, in 1860 and 1861; McKinlay, in 1861 and 1862; Landsborough, in 1862; and Stuart, also in 1862. Of McKinlay and of Landsborough I shall say very little. The former went from Adelaide to the Gulf of Carpentaria, and the latter from the Gulf of Carpentaria to Melbourne, both sent out by Australian committees to search for Burke who had not returned, and was never to return.

“Burke and Stuart are the two brave explorers of whom I am going to speak, and I will begin without further preamble.

“On August 20th, 1860, under the auspices of the Royal Society of Melbourne, an ex-Irish officer, and former police inspector at Castlemaine, named Robert O’Hara Burke, set out on his expedition. Eleven men went with him: William John Wills, a distinguished young astronomer; Dr. Beckler, a botanist; Gray; King, a young soldier of the Indian army; Landells; Brahe; and several sepoys. Twenty-five horses and twenty-five camels carried the explorers, their baggage, and provisions for eighteen months.

“The expedition was to make for the Gulf of Carpentaria on the northern coast, first following the Cooper River. They easily crossed the Murray and the Darling rivers, and arrived at Menindee Station, on the boundary of the colonies.

“There it was realized that the large baggage train was a source of great difficulty. This encumbrance, and a certain hardness of character in Burke, caused misunderstandings among the party. Landells, the manager of the camels, followed by some of the sepoys, separated himself from the expedition, and returned to the banks of the Darling. Burke continued his march northward. He descended toward Cooper Creek, sometimes through magnificent well watered pastures, and sometimes over stony tracts without any water. On November 20th, three months after his departure, he established a provision depot along the river.

“Here the explorers were detained for some time, unable to find a practicable route to the north on which they could be sure of a supply of water. After great difficulties they arrived at a camp, which they named Fort Wills. They built an enclosure surrounded by a palisade, halfway between Melbourne and the Gulf of Carpentaria. There, Burke divided his party into two parts. One, under command of Brahe, was to stay at Fort Wills for three months, or longer if their provisions held out, and await the return of the other party, which consisted of Burke, King, Gray, and Wills. They took with them six camels, and three months’ supplies — that is, three hundredweight of flour, fifty pounds of rice, fifty pounds of oatmeal, a quintal of dried horse meat, a hundred pounds of salt pork and bacon, and thirty pounds of biscuit — all to travel six hundred leagues1, there and back.

“These four men began. After the painful crossing of a stony desert they arrived on the Eyre River, at the extreme point reached by Sturt in 1845, and following as near as possible the 140th meridian, they kept going north.

“On January 7th they passed the tropic under a blazing sun. They continued north, deceived by disappointing mirages, often without water, sometimes refreshed by heavy storms. Here and there they met wandering natives, who they attempted to avoid. In short, they were little disturbed by the difficulties of a route which was not barred by lakes, rivers, or mountains.

“On January 12th some sandstone hills appeared in the distance, including Mount Forbes, and then a succession of granite chains called ‘ranges.’ There, travel became difficult. They made very little progress. The animals would go no further. Burke wrote ‘Still on the ranges — the camels sweating from fear!’ in his journal. Still, by dint of their efforts, they arrived on the banks of the Turner River, then on the upper course of the Flinders River between curtains of palm and eucalyptus trees, seen by Stokes in 1841, on its way to the Gulf of Carpentaria.

“The neighbourhood of the sea was indicated by a succession of marshes. One of the camels perished there. The rest refused to go further. King and Gray had to stay with them. Burke and Wills continued their journey to the north, and after great difficulties, only slightly described in their notes, they arrived at a tidal channel into which the sea flowed, but dense mangrove swamps barred them from the ocean, itself. It was February 11th, 1861.”

“So,” asked Lady Glenarvan, “these bold men couldn’t go any farther?”

“No, Madame,” said Paganel. “The swampy ground sank under their feet, and they were obliged to turn their thoughts to rejoining their companions at Fort Wills. A sad return, I assure you. Weak and exhausted, Burke and Wills dragged themselves back to the place where they had left Gray and King. Then the expedition, following the route they had come north by, made for Cooper’s Creek.

“The ups and downs, dangers and sufferings of this journey, we do not know exactly, because the notes are missing from the journals of the explorers, but it must have been terrible.

“At last, in April, three of them arrived in the Cooper Valley. Gray had died. Four camels had perished. Still, if Burke managed to reach Fort Wills, where Brahe and his depot of provisions were waiting for him, he and his companions were saved. They redoubled their efforts; they dragged themselves on for a few more days. On April 21st, they saw the palisades of the fort. They had reached it! But that very day, after five long months of hopeless waiting, Brahe had gone!”

“Gone!” cried young Robert.

“Yes, gone! The same day, by a deplorable fatality! The note left by Brahe was dated only nine hours ago! Burke could not hope to overtake him. The poor fellows fortified themselves a little from the cache of provisions left at the depot, but they had no means of transport, and 150 leagues2 still separated them from the Darling.

“It is then that Burke, contrary to the judgment of Wills, determined to try and reach the Australian settlement near Mount Hopeless, sixty leagues3 from Fort Wills. They set out. Of the two remaining camels, one perished in a marshy tributary of Cooper Creek; the other could not go a step farther; they had to kill it, and feed on its flesh. Soon all their food was gone. The three unfortunate wanderers were reduced to living on “nardoo,” an aquatic plant whose sporocarps are edible. Without the means to carry water across the desert, they dared not leave the banks of Cooper Creek. A fire burned their cabin, and camp effects. Now they were lost indeed! Nothing remained for them but to die!

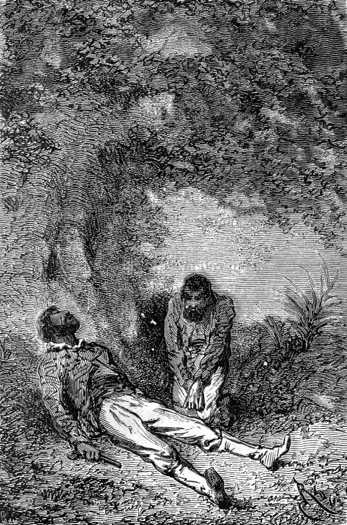

The death of Burke

“Burke called King to him. ‘I have only a few hours to live,’ he said. ‘Take my watch and my notes. When I am dead, I want you to place a pistol in my right hand, and to leave me just as I am, without burial!’ After this, Burke did not speak, and expired the next morning at eight o’clock.

“King, horrified and distraught, went to look for an Australian tribe. When he returned, Wills had just succumbed too. As for King, he was picked up by natives, and in September he was found by Mr. Howitt’s expedition sent in search of Burke, at the same time as the parties under McKinlay and Landsborough. Thus, of the four explorers, only one survived the journey across the continent of Australia.”

Paganel’s story left a painful impression in the minds of his listeners. They all thought of Captain Grant wandering, perhaps like Burke and his comrades, in the midst of this fatal continent. Had the castaways escaped the sufferings which had decimated those bold explorers? The analogy was so natural that tears came to Mary Grant’s eyes.

“My father! My poor father!” she whispered.

“Miss Mary, Miss Mary!” cried John Mangles. “To endure such hardships, you must be in the interior. Captain Grant must be among the natives like King. And like King, he will be saved. He has never been in such a sorry plight!”

“Never,” said Paganel, “and I repeat to you, my dear girl, the Australians are hospitable.”

“May God hear you,” said the girl.

“And Stuart?” asked Glenarvan, wishing to divert them from these sad thoughts.

“Stuart?” said Paganel. “Oh, Stuart had better luck, and his name is famous in Australian annals. As early as 1848, John McDouall Stuart, your countryman, my friends, as a prelude to his own travels, accompanied Sturt into the deserts north of Adelaide. In 1860, with only two men, he made an unsuccessful attempt to penetrate into the interior of Australia. He was not a man to be discouraged. In 1861, on January 1st, he left Chambers Creek at the head of eleven determined companions. But, his provisions exhausted, he was stopped only sixty leagues4 from the Gulf of Carpentaria. He was obliged to return to Adelaide without having crossed the vast continent. He resolved to tempt fortune again, and organized a third expedition, which this time would attain the ardently-desired goal.

“The Parliament of South Australia generously patronized this new expedition, and voted a subsidy of two thousand pounds sterling. Stuart took every precaution suggested to him by his earlier experience. The expedition consisted of ten men in all, most of them friends and comrades from his previous explorations, including Thring, Kekwick, Woodforde and Auld. They were joined by Waterhouse the naturalist. He took twenty skins of American leather, which could hold seven gallons each, and on April 5th, 1862, the party was assembled at Newcastle Waters, beyond the 18th parallel of latitude, the point which Stuart had never been able to go beyond. His route followed the 131st meridian, nine degrees west of that followed by Burke.

“Newcastle Waters was to be the base of future explorations. Stuart, surrounded by dense woods, vainly strove to reach the Victoria River, to the northwest. Impenetrable bush impeded all passage.

“Stuart resolved to try moving directly north, and he succeeded in moving his camp into the Hower Marshes. Then, bearing east, he reached Daly Waters, in the middle of grassy plains which he followed north for thirty miles.5

“The country was magnificent: its pastures would have been a joy and a fortune to a squatter, and the eucalyptus grew to a prodigious height. Stuart, marvelling, continued to advance. He reached the banks of the Strangway River and Roper Creek, discovered by Leichhardt. Their waters flowed amid palm trees worthy of this tropical region, and here he found native tribes who welcomed the explorers.

“From this point the expedition headed north-northwest, crossing a tract of sandstone and ferruginous rock they found the source of the Adelaide River, which falls into Van Diemen Gulf. They followed it across Arnhem’s Land, in the midst of cabbage-palms, bamboos, pines, and screw-palms. The Adelaide was widening, and its banks becoming marshy. The sea was near.

“On Tuesday, July 22nd, Stuart camped in the marshes of Fresh Water, blocked by the innumerable streams that cut his way. He sent three of his companions to look for a suitable path. The next day, sometimes turning aside at uncrossable creeks, sometimes bogging down in muddy ground, he reached some high plains covered with grass, where clumps of gum trees and trees with fibrous bark grew. There were flocks of geese, ibises, and wild water birds. Of natives, there was little sign, only smoke from distant camps.

“On July 24th, nine months after leaving Adelaide, at twenty minutes past eight in the morning, Stuart started north. He hoped to reach the sea that same day. The country became slightly elevated, dotted with iron ore, and volcanic rock; the trees became smaller, and began to look like coastal trees. A wide alluvial valley presented itself, bordered by a curtain of shrubs. Stuart distinctly heard the noise of the waves as they broke, but he said nothing to his companions. They entered a thicket, made almost impassable by wild vines.

“Stuart went on a few steps. He found himself on the shores of the Indian Ocean. ‘The sea! the sea!’ cried a stupefied Thring. The others ran forward, and three long hurrahs saluted the Indian Ocean.

“The continent had just been crossed for the fourth time!

“Stuart, following the promise he had made to Governor Sir Richard MacDonnell, dipped his feet and washed his face and hands in the waves of the sea. Then, he returned to the valley, and inscribed his initials, JMDS, on a tree. They camped beside a small stream.

“Next day, Thring went to see if they could reach the mouth of the Adelaide River from the southwest, but the ground was too swampy for the horses’ feet. It was necessary to abandon the idea.

…and at the top he fixed the Union Flag

“Stuart selected a tall tree in a clearing. He cut off the lower branches, and at the top he fixed a Union Flag, embroidered with his name. On the bark of the tree were cut these words, ‘Dig One Foot—S.’

“And if at some future day a traveller digs at the spot indicated, he will find a tin box,6 and in this box the document whose words are engraved on my memory:

South Australian Great Northern Exploring Expedition.

The exploring party, under the command of John McDouall Stuart, arrived at this spot on the 25th day of July 1862 having crossed the entire Continent of Australia from the Southern to the Indian Ocean, passing through the Centre. They left the City of Adelaide on the 26th day of October 1861 and the most northern station of the colony on the 21st day of January 1862. To commemorate this happy event, they have raised this flag bearing his name. All well. God save the Queen!

‘’Followed by the signatures of Stuart and his companions.

“This was a great event that had a tremendous impact, worldwide.”

“And did these brave men live to rejoin their friends in the South?” asked Lady Helena.

“Yes, Madame, all,” said Paganel. “But not without undergoing terrible trials. Stuart suffered most. His health was seriously compromised by scurvy when he resumed his journey to Adelaide. By the beginning of September his illness had made such progress that he did not think he would reach the inhabited districts again. He could not sit in the saddle; he travelled lying in a stretcher suspended between two horses. At the end of October he was extremely ill, and spitting blood. They killed a horse to make him a broth. October 28th he thought death was at hand when a salutary crisis saved him, and on December 10th the whole little troop reached the first settlements.

“On December 17th Stuart received an enthusiastic welcome in Adelaide. But he had not recovered his health, and after receiving the gold medal of the Geographical Society, he took passage in the Indus for his beloved Scotland, his native land, where we shall see him on our return.”,7

“He was a man who possessed moral courage to the highest degree,” said Glenarvan, “And that, even more than physical strength, leads to the accomplishment of great things. Scotland is rightly proud to count him among her children.”

“Has no explorer attempted further discoveries, since Stuart?” asked Lady Helena.

“Yes, Madame,” replied Paganel. “I have often spoken to you of Leichhardt. He had already made a remarkable exploration of Northern Australia, in 1844. In 1848 he undertook a second expedition, to the northeast. That was seventeen years ago, and he has not been seen since. Last year the famous botanist, Dr. Mueller, of Melbourne, created a public subscription to defray the expenses of an expedition to search for him. The requisite sum was quickly raised, and a party of courageous squatters, commanded by the bold and intelligent Mclntyre, started from the pasturages of the Paroo river, on June 21st, 1864. At this moment he has probably penetrated far into the interior of the continent, in his search for Leichhardt. May he succeed, and may we too, like him, find again the friends so dear to us!”

Thus ended the geographer’s story. It was late. Paganel was thanked, and shortly later all were peaceably sleeping, while the clock-bird, hidden in the foliage of the white gum trees, kept time all through the still night.

1. 1,500 miles, 2,400 kilometres — DAS

2. 375 miles, 600 kilometres — DAS

3. 150 miles, 240 kilometres — DAS

4. 150 miles, 240 kilometres — DAS

5. 12 leagues, 50 kilometres — DAS

6. The tree on which Stuart carved “JMDS” was located in 1883. The flag tree, and its tin box, have not been found. — DAS

7. James Paganel was able to see Stuart on his return to Scotland, but he did not long enjoy the company of this famous traveller. Stuart died on June 5th, 1866, in a modest house in Nottingham Hill.