A terrible accident had occurred

The Major had felt some apprehension as he watched Ayrton depart the Wimmera camp to go look for a blacksmith at Black Point Station, but he kept his misgivings to himself, and didn’t breathe a word to anyone. He contented himself with watching the neighbourhood of the river. The tranquility of the glades was undisturbed, and after a few hours of night the sun re-appeared on the horizon.

Glenarvan’s only fear was that Ayrton might return alone. If they failed to find a workman, the wagon could not resume the journey. This might detain them for many days, and Glenarvan, impatient to reach his goal, couldn’t tolerate any delay.

Fortunately, Ayrton lost neither time nor his way. He appeared next morning at daybreak, accompanied by a man who said he was a blacksmith from Black Point Station. He was a tall, powerful fellow, but with low, bestial, unfavourable features. But that was of no concern, provided he knew his business. He scarcely spoke, and did not waste his breath in useless words.

“Is he a good workman?” John Mangles asked the quartermaster.

“I know no more about him than you do, Captain,” said Ayrton, “but we shall see.”

The blacksmith set to work repairing the wagon, and it quickly became evident that he knew his trade. He worked skilfully and with uncommon energy. The Major observed that the flesh of his wrists was deeply furrowed, showing a black collar of bruising. It was the mark of a recent injury which the sleeve of an old woollen shirt could not conceal. MacNabbs questioned the blacksmith about these sores, which must have been painful, but the man continued his work without answering. Two hours later, the damage to the wagon had been repaired.

Glenarvan’s horse was re-shod even quicker. The blacksmith had the foresight to bring horseshoes with him. The Major noticed an unusual feature of these shoes: a deep clover design cut into their bottoms. MacNabbs pointed it out to Ayrton.

“It’s the Black Point brand,” said the quartermaster. “That enables them to track any horses that may stray from the station, and prevents their being mixed with other herds.”

The new shoes were quickly fitted to the horse’s hooves. The blacksmith claimed his wage, and left without uttering four words.

Half an hour later, the travellers were on the move again. Beyond the curtains of mimosas bordering the river stretched a wide open country, which quite deserved its epithet of “open plain.” Some fragments of quartz and ferruginous rock lay among the scrub and the tall grass, and there were fenced in areas where many flocks of sheep grazed. Some miles further the wheels of the wagon ploughed deep into the lacustrine soil, where irregular creeks murmured, half hidden among giant reeds. They skirted vast salty lagoons, rapidly evaporating in the day’s heat. The journey was effortless and trouble free.

Lady Helena invited the horsemen of the party to take turns visiting her, as her salon was very small. But each of them was happy to take a break from riding, and amuse himself in conversation with this amiable woman. Lady Helena, assisted by Miss Mary, did the honours of their travelling house with perfect grace. John Mangles was not forgotten in these daily invitations, and his serious conversation was not unpleasing. Quite the contrary.

They cut diagonally across the mail road from Crowland to Horsham. This was a very dusty road, little used by pedestrians. They skirted the rumps of some low hills at the boundary of Talbot County, and in the evening the travellers reached a point about three miles above Maryborough. A fine rain was falling, which in any other country would have soaked the ground, but here the air absorbed the moisture so rapidly, that it was scarcely an inconvenience.

Next day, December 29th, the march was somewhat slowed by a succession of small hills, resembling a miniature Switzerland. It was a constant repetition of up hill and down, on rough roads that jolted the wagon so unpleasantly that the ladies preferred to leave it, and walk part of the way.

At eleven o’clock they arrived at the large town of Carisbrook. Ayrton was of the opinion that the wagon might be delayed going through town, and suggested going around it. Glenarvan agreed, but Paganel, always eager for novelties, wanted to visit Carisbrook. He was allowed to do so, while the wagon went slowly around it.

As usual, Paganel took Robert with him. Their visit to the town was brief, but it sufficed to give him an impression of a typical Australian town. There was a bank, a court-house, a market, a school, a church, and a hundred or so perfectly uniform brick houses. The whole town was laid out in rectangles, crossed with parallel streets in the English fashion. Nothing could be simpler, or less attractive. As the town grew, they lengthened the streets as you lengthen the trousers of a growing child, and thus the primitive symmetry remains undisturbed.

Carisbrook was full of activity, a remarkable feature in these new towns. In Australia it seems that towns grow like trees in the heat of the sun. Busy people ran in the streets. Gold shippers crowded the exchange offices. The precious metal, escorted by the local police, was brought in from the mines at Bendigo and Mount Alexander. All of this little world was so absorbed in its own interests, that the strangers passed unobserved amid the busy population.

After an hour of looking around Carisbrook, the two visitors rejoined their companions, passing though the highly cultivated environs of the town. This was followed by long stretches of prairie known as the “Low Level Plains,” dotted with countless sheep, and shepherds’ huts. Then they came to a stretch of desert, without any transition, but with that abruptness peculiar to Australian nature. The Simpson Hills and Mount Tarrengower marked the point where the southern boundary of the Loddon district cuts the 144th meridian.

None of the aboriginal tribes living in the wild had been encountered so far. Glenarvan wondered if the Australians were wanting in Australia, as the Indians had been wanting in the Argentinian Pampas, but Paganel told him that, in this latitude, the natives were to be found in the Murray Plains, a hundred miles to the east.

“We are approaching the gold district,” he said. “In two days we shall cross the rich region of Mount Alexander. This is where the swarm of miners came in 1852; the natives fled to the wilderness of the interior. We are in civilized country, even if it doesn’t look like it. Later today we should cross the railway which connects the Murray with the sea. But I must confess that a railway in Australia does seem to me an astounding thing!”

“And why is that, Paganel ?” asked Glenarvan.

“Why? Because it chafes! Oh, I know you English are accustomed to colonizing distant possessions. You, with your electric telegraphs and World Exhibitions, even in New Zealand.1 You think it is all quite natural. But it dumbfounds the mind of a Frenchman like myself, and confuses all his notions of Australia!”

“Because you look to the past, and not at the present,” said John Mangles.

“Perhaps,” said Paganel. “But the locomotives chuffing across wild plains, spirals of steam winding through the branches of mimosa and eucalyptus; echidnas, platypuses, and emus fleeing before speeding trains; savages taking the 3:30 express to go from Melbourne to Kyneton, to Castlemaine, to Sandhurst, or to Echuca: that sort of thing is erasing everything that isn’t English, or American from the world. With the coming of your railways, the poetry of the wilderness vanishes.”

“What does it matter as long as we make progress?” asked the Major.

A loud whistle interrupted the discussion. The party was within a mile of the railway. A locomotive coming slowly from the south stopped just where the road being followed by the wagon crossed the railway.

This railway, as Paganel had said, connected the capital of Victoria to the Murray, the largest river in Australia. This immense watercourse, discovered by Sturt in 1828, has its source in the Australian Alps. Augmented by its tributaries, the Lachlan and the Darling, it forms the northern boundary of the province of Victoria, and empties into Encounter Bay, near Adelaide. It flows through a rich and fertile country, and squatter stations multiply along its course, thanks to the easy communication with Melbourne established by the railway.

This railway was then operating over a distance of 105 miles2 between Melbourne and Sandhurst, serving Kyneton and Castlemaine. The line, still under construction, continued for another seventy miles as far as Echuca, capital of the Riverine colony, founded that year on the Murray.

The 37th parallel intersected the track a few miles above Castlemaine, at Camden Bridge over the Loddon River, one of the many tributaries of the Murray.

Ayrton directed the wagon toward the bridge. The horsemen galloped ahead, attracted by curiosity over what was happening.

A considerable crowd was gathering at the railway bridge. The people from the neighbouring stations had left their houses, and the shepherds their flocks, and crowded the approaches to the railway. Every now and then someone shouted “At the railway! At the railway!”

Something serious must have occurred to produce so much agitation. Perhaps some great catastrophe.

A terrible accident had occurred

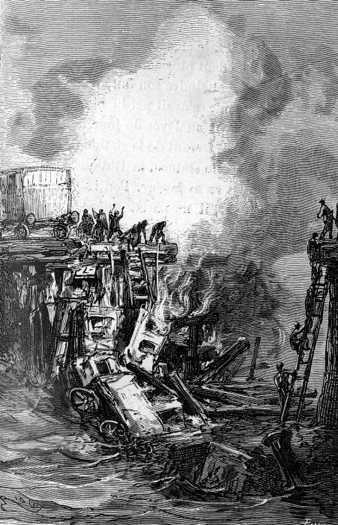

Glenarvan, followed by the rest, urged his horse on. In a few minutes he arrived at Camden Bridge, and became aware of the cause of so much excitement. A terrible accident had occurred. Not a collision, but a derailment, and fall which recalled the worst disasters of the American railways. The river crossed by the railway was full of the wreckage of several carriages, and the locomotive. The weight of the train had been too much for the bridge, or the train had gone off the rails. Either way, five out of six carriages had fallen into the bed of the Loddon, dragged down by the locomotive. Only the last carriage, miraculously preserved by the breaking of the coupling, remained on the rails, three feet from the abyss. Below it was a sinister pile of warped and blackened axles, shattered carriages, twisted rails, and charred sleepers. The boiler, burst by the shock, had scattered its plates to enormous distances. From this shapeless mass of ruins a few flames and wisps of steam and black smoke still rose. After the fall had come an even more horrible fire. Large streaks of blood, scattered limbs, and charred corpses were scattered around. No one could guess how many victims might lay under those ruins.

Glenarvan, Paganel, the Major, and Mangles mingled with the crowd, listening to what was being said. Everyone was trying to account for the disaster, while doing their utmost to save what could be saved.

“The bridge must have collapsed,” said one.

“Collapsed!” said another. “The bridge is still intact! They must have forgotten to close it to let the train pass. That is all.”

It was, indeed, a swing bridge which opened for the convenience of the river traffic. Had the guard, in an unpardonable act of negligence, forgotten to close it? And had the train, coming on at full speed, plunged into the bed of the Loddon? This hypothesis seemed very likely, for although one half of the bridge lay beneath the ruins of the train, the other half, drawn up to the opposite shore, hung by its chains, still undamaged. No one could doubt that negligence by the guard had caused the catastrophe.

The accident had occurred in the night to the №37 express train, which had left Melbourne at 11:45 in the evening. About a quarter past three in the morning, twenty-five minutes after leaving Castlemaine station, it arrived at Camden Bridge, where the terrible disaster occurred. The passengers and conductors of the last, and only remaining, carriage immediately tried to obtain help, but the telegraph line had been broken by the accident. Several poles were lying on the ground. It took three hours for the authorities from Castlemaine to reach the scene of the incident, and it was six o’clock in the morning when the rescue party was organized under the direction of Mr. Mitchell, the Surveyor General of the colony, accompanied by a detachment of police, commanded by an inspector. The squatters and their hands lent their aid, first working to extinguish the fire which raged uncontrollably through the wreckage. A few unrecognizable bodies lay on the slope of the embankment, but from that blazing furnace no living being could be saved. The fire had done its destructive work too quickly. Of the passengers on the train, the total number of which was unknown, only the ten from the last carriage had survived. The railway authorities sent an emergency locomotive to bring them back to Castlemaine.

Lord Glenarvan, having introduced himself to the Surveyor General, was talking with him and the police inspector. The inspector was a tall, thin man, imperturbably cool, and, whatever he may have felt, allowed no trace of it to appear on his face. He contemplated this calamity as a mathematician does a problem. He was seeking to solve it, and to find the unknown.

“This is a great misfortune,” said Glenarvan.

“Better than that, My Lord,” said the inspector.

“Better than that?” Glenarvan was shocked by the phrase. “What is better than a misfortune?”

“A crime!” said the inspector quietly.

Glenarvan, without being put off by the impropriety of the statement, turned to Mr. Mitchell, questioning him with his eyes.

“Yes, My Lord,” said the Surveyor General. “Our investigation has led us to the certainty that this catastrophe is the result of a crime. The last luggage car was looted. The surviving passengers were attacked by a gang of five or six bandits. The bridge was intentionally opened, and not left open by the negligence of the guard. Connecting this fact with the guard’s disappearance, it must be concluded that the wretched fellow was an accomplice of these criminals.”

The inspector shook his head at this last inference.

“You do not agree with me?” said Mr. Mitchell.

“No, not as to the complicity of the guard.”

“But with his complicity,” said the Surveyor General, “we may attribute the crime to the savages who wander in the Murray countryside. Without the guard, these natives could never have opened the bridge. They know nothing of its mechanism.”

“Correct,” said the inspector.

“Now,” said Mr. Mitchell, “it is undisputed that, by the evidence of a boatman who passed Camden Bridge at 10:40 in the evening, that the bridge was closed after he passed.”

“True.”

“Well, after that, I cannot see any doubt as to the complicity of the guard.”

The inspector shook his head.

“But then sir,” said Glenarvan, “you don’t attribute the crime to the natives?”

“Not at all.”

“Who then?”

It was the body of the guard

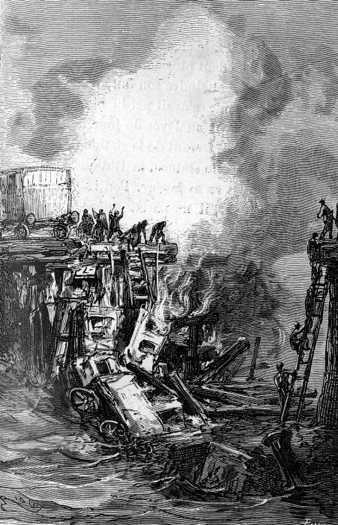

They were interrupted by a growing uproar, beginning half a mile up the river. A crowd was gathering, and grew quickly as it came closer. They soon reached the bridge, and in their midst were two men carrying a corpse. It was the body of the guard, already cold. He had been stabbed through the heart. The murderers had no doubt hoped that dragging his body away from Camden Bridge would mislead the police during their initial investigation. This discovery justified the doubts of the inspector. The natives had nothing to do with the crime.

“Those who dealt that blow,” said the inspector, “are people familiar with the use of this little instrument.” He produced a pair of “darbies,” a kind of handcuff made of a double ring of iron secured by a lock. “Before long, I shall have the pleasure of presenting them with these bracelets as a New Year’s gift.”

“Then you suspect—”

“People who ‘travelled free in Her Majesty’s ships.’”

“What! Convicts?” cried Paganel, who recognized the euphemism employed in the Australian colonies.

“I thought that convicts were not allowed in the province of Victoria,” said Glenarvan.

“Bah!” said the inspector. “If they have no right, they take it! They escape sometimes, and, if I am not greatly mistaken, this lot have come straight from Perth, and, take my word for it, they will soon be there again.”

Mr. Mitchell nodded acquiescence to the words of the inspector.

The wagon was approaching the railroad crossing. Glenarvan wished to spare the ladies the horrible spectacle at Camden Bridge. He took courteous leave of the Surveyor General, and signalled for the rest to follow him. “There is no reason to delay our journey.”

When they reached the wagon, Glenarvan merely stated to Lady Helena that there had been a railway accident, without saying what part the crime had played in the catastrophe. He also didn’t mention the presence of a band of convicts in the neighbourhood, reserving that piece of information for Ayrton’s ear, alone. The little troop crossed the railway a few hundred fathoms below the bridge, and resumed their eastward journey.

1. The New Zealand Exhibition of 1865 — DAS

2. 42 leagues, 170 kilometres — DAS