Lord Glenarvan and his companions arrived inside the pā

An unfathomable chasm twenty-five miles long, and twenty wide, was formed long before historical times by a collapse of caverns in the middle of the trachytic lavas of the centre of the island. The waters from the surrounding peaks slowly filled this enormous cavity to become a lake, an abyss that no sounding line has yet to plumb.1

Such is the strange Lake Taupo, 1,170 feet above sea level, and surrounded by a cirque of mountains 2,400 feet high. To the west, the shore is dominated by sheer rock cliffs; to the north are some distant tree covered peaks; to the east, a wide beach crossed by a road decorated with pumice stones which shine under a lattice of bushes; to the south, volcanic cones rise behind a foreground of forests. In the heart of all this majesty lies a vast expanse of water, whose storms rival the hurricanes of the oceans.

All this region boils like an immense cauldron suspended on subterranean flames. The ground quivers under the caresses of the central fires. Steam issues from the ground in many places. The crust of the earth splits in violent cracks like dough that has risen too much, and no doubt this plateau would be ruined in an incandescent furnace if, twelve miles further, the imprisoned vapours could not find an exit through the craters of Tongariro.

From its north rim, this volcano appeared filled with smoke and flame above small lava domes. Mount Tongariro was part of a complicated system of volcanoes. Behind it, isolated in the midst of a plain, Mount Ruapahu rose nine thousand feet in the air, its peak lost amid of the clouds. No mortal has set foot on its inaccessible cone; no human eye has ever probed the depths of its crater,2 while, three times in twenty years, Messrs. Bidwill and Dyson, and more recently Dr. von Hochstetter, have measured the more accessible peaks of Tongariro.

These volcanoes have their legends, and, in any other circumstances, Paganel would not have failed to tell them to his companions. He would have told them of the argument that happened one day between Tongariro and Taranaki, then his neighbour and friend, over the matter of a woman. Tongariro, who has a hot head, like all volcanoes, went so far as to hit Taranaki. Taranaki, beaten and humiliated, fled through the valley of the Whanganui, dropped two pieces of mountain on the way, and reached the shores of the sea, where he rises solemnly under the name of Mount Egmont.

But Paganel was hardly in a position to tell, nor were his friends in a mood to listen to him. They silently watched the northeastern shore of Lake Taupo where this most disappointing fate had just led them. Reverend Grace’s mission to Pūkawa, on the western shores of the lake, no longer existed. The minister had been driven far from the heart of the insurrection by the war. The prisoners were alone, abandoned, at the mercy of Māori greedy for reprisals, and in this wild portion of the island where Christianity has never penetrated.

Kai-Kúmu, leaving the waters of the Waikato, crossed the little cove which serves as a funnel to the river, doubled a sharp promontory, and landed on the eastern shore of the lake, at the foot of the first ripples of Maunganamu, an 1,800 foot, extinct volcano. There, fields of Phormium, what the natives call harakeke, the precious flax of New Zealand, were spread out. Nothing is is wasted of this useful plant. Its flower provides a kind of excellent nectar; its stem produces a gummy substance, which replaces wax or starch; its leaves, more useful still, lend themselves to many transformations: fresh, it serves as paper; desiccated, it makes an excellent tinder; cut, it is made into ropes, cables and nets; divided into filaments and combed, it becomes a blanket or mantle, mat or loincloth, and dyed red or black, it dresses the most elegant Māori.

This precious Phormium is found everywhere in the two islands, from the shores of the sea, to the banks of the rivers and lakes. Here its wild bushes covered entire fields; its reddish brown, agave-like flower stalks rose out of an inextricable clutter of its long leaves, which formed a trophy of sharp blades. Graceful birds, nectar eaters, common in the Phormium fields, flew in numerous flocks and delighted in the honeyed juice of the flowers.

Troops of black plumed ducks, dappled with grey and green, bobbed in the waters of the lake. This species was easily domesticated.

A quarter of a mile away, on an escarpment of the mountain, appeared a pā, a Māori fortress placed in an impregnable position. The prisoners were unloaded one by one, their feet and hands freed, and led toward it by the warriors. The path to the fortification crossed Phormium fields, and a grove of beautiful trees: kahikatea, evergreens with red berries; Cordyline australis, the ti of the natives, and commonly called the cabbage tree by the Europeans; and huious which provides black dye for fabrics. Large doves with a metallic sheen, ashen kōkako, and a world of starlings with reddish wattles, flew away at the approach of the natives.

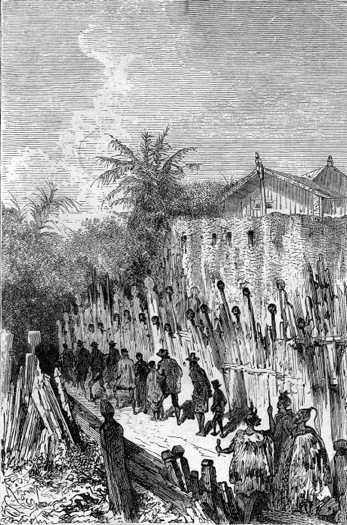

Lord Glenarvan and his companions arrived inside the pā

After a long detour, Glenarvan, Lady Helena, Mary Grant and their companions arrived inside the pā.

This fortress was defended by an outer palisade, fifteen feet high; a second line of stakes, then a wicker fence pierced with loopholes, enclosing an inner space — the plateau of the pā — in which Māori buildings and about forty huts were arranged symmetrically.

On arriving there, the captives were horribly impressed by the sight of the heads that adorned the posts of the inner enclosure. Lady Helena and Mary Grant averted their eyes with more disgust than horror. These heads had belonged to fallen enemy leaders, whose bodies had served as food for the victors.

The geographer recognized them as such, from their empty eye sockets.

The eyes of a defeated chief are eaten. The head is then prepared by removing its brain and stripping away the skin. The nose is held in shape by small strips of wood, the nostrils stuffed with Phormium, the mouth and the eyelids sewn closed, and the head is smoked in an oven for thirty hours. Thus prepared, it is preserved indefinitely without alteration or wrinkle, to make a trophy of victory.

Often the Māori keep the heads of their own chiefs, but in this case, the eyes stay in their sockets and look out at the spectators. The New Zealanders display these relics with pride; they offer them up for the admiration of young warriors, and pay them a tribute of veneration with solemn ceremonies.

But, in Kai-Kúmu’s pā, the enemy’s heads alone adorned this horrible museum, and no doubt more than one English head with empty sockets had been added to the collection of the Māori chief.

Kai-Kúmu’s house rose between several huts of lesser importance at the bottom of the pā, in front of a large open field, which some Europeans called “the field of battle.” This house was built of poles caulked with intertwining branches, and internally lined with mats of Phormium. Twenty feet long, fifteen feet wide, and ten feet high, Kai-Kúmu’s house was a dwelling of three thousand cubic feet. It does not take more to house a Māori leader.

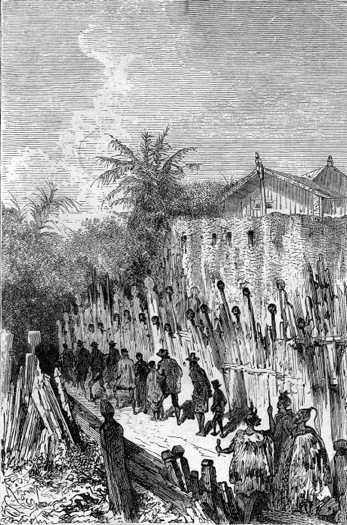

A single opening gave access to the house; a swinging flap made of thick vegetable fibre served as a door. Above, the roof extended in eaves away from the walls. Some carved figures at the end of the rafters adorned the house, and the whatitoka, or doorway offered a curious confusion of foliage, symbolic figures, monsters, and foliated scrolls, created by the chisel of native decorators for the visitors’ admiration.

Inside the house, the dirt floor was raised half a foot above the ground. A few reed shelves, and dry fern mattresses covered with a mat woven with the long, flexible leaves of Typha, served as beds. In the middle, a stone hole formed the hearth, and in the roof, a second hole served as a chimney. The smoke, when it was thick enough, finally decided to take advantage of this escape, but not without placing a varnish of the most beautiful black on the walls of the house.

Next to the hut stood the storehouses which contained the chief’s provisions, his harvest of Phormium, potatoes, taros, edible ferns, and the ovens in which the various foods were cooked in contact with heated stones. Further on, in small enclosures, were pigs and goats, rare descendants of the useful animals imported by Captain Cook. Dogs ran here and there, begging for their meagre food. They were poorly kept for beasts that daily serve as food for the Māori.

Glenarvan and his companions had taken in this scene at a glance. They waited near an empty house for the pleasure of the chief, while being exposed to the insults of a band of old women. This band of harpies surrounded them, threatened them with their fists, howled, and shouted. A few words of English escaping from their rude lips made it clear that they were demanding immediate vengeance.

In the midst of these shouts and threats, Lady Helena, seemingly tranquil, affected a calm that could not be in her heart. This brave woman contained herself with heroic efforts, to allow Lord Glenarvan to keep his own composure. Poor Mary Grant felt faint, and John Mangles supported her, ready to die defending her. Their companions variously endured this deluge of invective: with indifference, like the Major, or with growing irritation, like Paganel.

Glenarvan, wishing to relieve Lady Helena from the assault of these old shrews, walked straight to Kai-Kúmu, and pointing to the hideous group said “Send them away.”

The Māori chief stared at his prisoner without answering him; then, with a gesture, he silenced the screaming horde. Glenarvan bowed, as a sign of thanks, and slowly returned to his place among his people.

At this moment, a hundred New Zealanders were gathered in the pā, old men, adults, and youngsters. Some quiet, but dispirited, waiting for Kai-Kúmu’s orders, the others engaging in the most violent sorrow; they were crying for their parents or friends fallen in the latest battles.

Kai-Kúmu alone, of all the chiefs who had answered the call of William Thompson, returned to the districts of the lake, and was the first to tell his tribe of the defeat of the national insurrection, beaten in the lowlands of Waikato. Of the two hundred warriors who, under his command, ran to the defence of the land, a hundred and fifty were missing on their return. Even if some were prisoners of the invaders, how many — lost on the field of battle — were never to return to the land of their ancestors?

This explained the deep desolation that struck the tribe at the arrival of Kai-Kúmu. This was the first news to arrive of the latest defeat.

In savages, sorrow always manifests itself in physical demonstrations. Relatives and friends of dead warriors, especially women, tore their faces and shoulders with sharp shells. The blood gushed and mingled with their tears. The deep incisions marked their great despair. The poor Māori women, bloody and maddened, were horrible to see.

Their despair was increased even more for another reason, very serious in the eyes of the natives. Not only was the parent or the friend they were mourning no longer alive, but his bones couldn’t be placed in the family’s tomb. The disposition of these remains is regarded, in the Māori religion, as indispensable to their destinies in the afterlife. Not the perishable flesh, but the bones, which are carefully collected, cleaned, scraped, polished, even varnished, and finally deposited in the Údu pá, or “the house of glory.” These tombs are decorated with wooden statues that reproduce with perfect fidelity the tattoos of the deceased. But today the tombs would remain empty, the religious ceremonies would not be fulfilled, and the bones spared from the teeth of wild dogs would whiten without burial on the field of battle.

Their sorrow redoubled. The threats of the women against the Europeans overcame the imprecations of the men. More insults burst forth, the gestures became more violent. This outcry might be followed by acts of brutality.

Kai-Kúmu, fearing to be overwhelmed by the fanatics of his tribe, had his captives taken to a sacred place at the rear of the pā, on a steep plateau. This hut backed against a massif that towered a hundred feet above the rest of the pā, which fell away in steep slopes to the sides. In this Ware Atua, a consecrated house, the priests or the arijis taught the Māori of a god in three persons, the father, the son, and the bird or the spirit. The large well-built house contained the holy food chosen for Māui-Rangi-Ranginui to eat through the mouths of their priests.3

There the captives, momentarily sheltered against the native fury, lay on Phormium mats. Lady Helena, her strength exhausted, her moral energy vanquished, sank into her husband’s arms. Glenarvan, pressing her to his chest, repeated “Courage, my dear Helena. Heaven will not desert us!” to her.

Robert climbed on Wilson’s shoulders

They were barely shut in when Robert climbed on Wilson’s shoulders, and managed to slide his head through a gap between the roof and the wall, where rosaries of amulets hung. From there, he could see across the pā to Kai-Kúmu’s hut.

“They are gathered around the chief,” he said in a low voice. “They wave their arms … they scream … Kai-Kúmu wants to speak …”

The child was silent for a few minutes, then he went on.

“Kai-Kúmu speaks … the savages are calming down … they are listening to him …”

“Of course,” said the Major. “This chief has a personal interest in protecting us. He wants to exchange his prisoners for the leaders of his tribe! But will his warriors consent?”

“Yes! … They listen to him …” said Robert. “They scatter … some return to their huts … the others leave the fortress …”

“Is that right?” asked the Major.

“Yes, Mr. MacNabbs,” said Robert. “Kai-Kúmu alone remains, with the warriors of his boat. Ah! One of them comes to our hut.”

“Come down, Robert,” said Glenarvan.

At this moment Lady Helena, who had risen, seized her husband’s arm. “Edward,” she said firmly, “neither Mary Grant nor I must fall alive into the hands of these savages!”

And, with these words spoken, she handed Glenarvan a loaded revolver.

“A weapon!” exclaimed Glenarvan, a flash of lightning in his eyes.

“Yes! The Māori did not search their women prisoners! But this weapon is for us, Edward, not for them!”

“Glenarvan,” said MacNabbs quickly, “hide that revolver! It’s not yet time.”

The revolver disappeared under the Lord’s clothes. The mat that closed the entrance to the hut was raised. A native appeared.

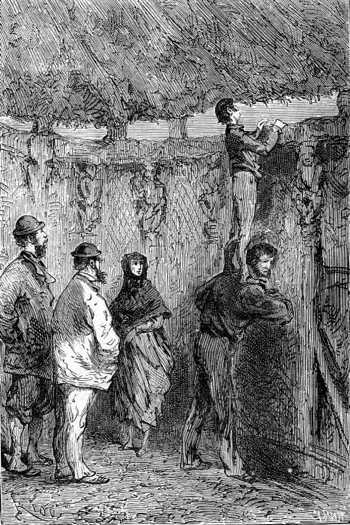

He motioned the prisoners to follow him. Glenarvan and his people crossed the pā in a tight group, and stopped in front of Kai-Kúmu.

The principal warriors of his tribe were gathered around their chief. Among them was the Māori whose boat joined Kai-Kúmu’s at the confluence of the Pokaiwhenua and the Waikato. He was a man of forty, vigorous, fierce, and cruel. He was named Kára-Téte, that is to say, “the irascible” in the Māori language. Kai-Kúmu treated him with some respect, and, by the fineness of his tattoos, it could be seen that Kára-Téte was high in the tribes. A careful observer would have also guessed that there was a rivalry between these two leaders. The Major observed that the influence of Kára-Téte annoyed Kai-Kúmu. They both commanded important tribes of Waikatos with equal authority, but during their conversation, Kai-Kúmu’s mouth smiled, but his eyes betrayed a deep enmity.

Kai-Kúmu questioned Glenarvan. “You are English?” he asked.

“Yes,” replied the Lord without hesitation, for that nationality would render an exchange easier.

“And your companions?” asked Kai-Kúmu.

“My companions are English, like me. We are travellers, shipwrecked. But, if you want to know, we did not take part in the war.”

“It does not matter!” said Kára-Téte roughly. “All English are our enemies. You have invaded our island! You have burned our villages!”

“They were wrong!” said Glenarvan in a grave voice. “I say this because I believe it, and not because I am in your power.”

“Listen,” said Kai-Kúmu, “the Tohunga, the high priest of Nui Atua4 , fell into the hands of your brothers; he is a prisoner of the Pākehā5. Our god commands us to redeem his life. I would have liked to tear your heart out, I would have wanted your head and the heads of your companions to be eternally suspended on the posts of this palisade! But Nui Atua spoke.”

In speaking thus, Kai-Kúmu, hitherto master of himself, trembled with anger, and his countenance was imbued with ferocious exaltation.

Then, after a few moments, he went on coldly “Do you think the English will exchange our Tohunga for you?”

Glenarvan hesitated to answer, and watched the Māori chief carefully.

“I do not know,” he said, after a moment’s silence.

“Speak,” said Kai-Kúmu. “Is your life worth the life of our Tohunga?”

“No,” replied Glenarvan. “I am neither a leader nor a priest among mine!”

Paganel, stunned by this answer, looked at Glenarvan with profound astonishment.

Kai-Kúmu also seemed surprised. “So, you do not know?” he said.

“I do not know,” repeated Glenarvan.

“Your people will not accept you in exchange for our Tohunga?”

“Only me? No,” repeated Glenarvan. “All of us, maybe.”

“The Māori,” said Kai-Kúmu, “trade prisoners head for head.”

“Offer these women first in exchange for your priest,” said Glenarvan, pointing to Lady Helena and Mary Grant.

Lady Helena wanted to run to her husband. The Major held her back.

“These two ladies,” said Glenarvan, bowing with respectful grace to Lady Helena and Mary Grant, “rank high in their country.”

The warrior looked coldly at his prisoner. A perverse smile passed on his lips; but he repressed it almost immediately, and replied in a voice which he scarcely contained. “Do you hope to deceive Kai-Kúmu by false words, cursed European? Do you think that Kai-Kúmu’s eyes cannot read your hearts?”

And, pointing to Lady Helena “Here is your wife!” he said.

“No! Mine!” exclaimed Kára-Téte. Then, pushing back the prisoners, his hand came down on Lady Helena’s shoulder, who turned pale under this touch.

“Edward!” cried the distraught woman.

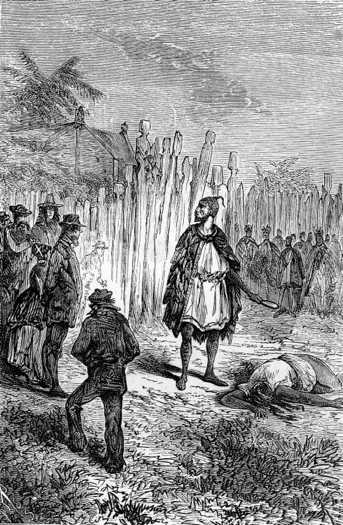

Glenarvan, without uttering a single word, raised his arm. A shot rang out. Kára-Téte fell dead.

At this detonation, a flood of natives came out of the huts. The pā filled in an instant. One hundred arms were raised against Glenarvan and the revolver was torn from his hand.

“Tapu! Tapu!” called out Kai-Kúmu

Kai-Kúmu gave Glenarvan a strange look; then, with one hand raised over Glenarvan, and the other toward the onrushing crowd he called out “Tapu! Tapu!”6 in a dominating voice.

At this word, the crowd stopped before Glenarvan and his companions, momentarily protected by a supernatural power.

A few moments later, they were escorted back to the Ware Atua, which served as their prison. But Robert Grant and Jacques Paganel were no longer with them.

1. The entire Lake Taupo region is the caldera of a super-volcano, and while the lake may have been unplumbed in Verne’s time, it isn’t really all that deep, with an average depth of 110 metres, and a maximum depth of 186 metres — DAS

2. This “inaccessible cone” was first climbed in 1879. Now there are ski resorts on its slopes, and it doubled for Mount Doom in the Lord of the Rings films — DAS

3. Verne seems to be trying too hard to draw parallels between Māori and Christian mythology here, with this parallel between some Māori gods and the Christian Trinity. In Māori mythology Māui is a hero demigod, who, among other things, pulled the Island of Te Ika-a-Māui (Māui’s fish) out of the sea when fishing one day. Rangi and Ranginui are alternate names of the sky father creator god. (Meaning “sky” and “great sky” respectively) — DAS

4. Name of the Māori god.

Not really. The Māori have several gods, but “Nui Atua” doesn’t seem to be one of them. Literally it means “great god.” Since the introduction of Christianity, “Atua” has come to mean the Christian God — DAS

5. Europeans.

6. Verne had Kai-Kúmu saying “Tabou” here, but as that is a loan word into French from the Polynesian/Māori “Tapu.” I kept Kai-Kúmu speaking Māori — DAS