This was the signal to begin a terrible scene of cannibalism

Kai-Kúmu, following a rather common practice in New Zealand, was the ariki as well as the chief of the tribe. He was clothed with the dignity of a priest, and as such he could extend the superstitious protection of the tapu over persons or objects.1

The tapu, common to Polynesian peoples, has the immediate effect of prohibiting any use of, or relationship with, the object or person under the tapu. According to the Māori religion, anyone who lays a sacrilegious hand on what has been declared tapu could be punished with death by an angry god. And if the god is slow to avenge their own insult, the priests can step in to do it for them.

The tapu may be applied by a chief for political reasons, or it may come about from the ordinary events of everyday life. In many circumstances a native is tapu for a few days when he cuts his hair, when he has just received a tattoo, when he builds a canoe, when he builds a house, when he has a life-threatening illness, and when he is dead. If over consumption threatens to depopulate a river of its fish, or to ruin the future production of a field of sweet potatoes, these objects are struck with a tapu protection for economic reasons. If a leader wants to remove unwelcome guests from his house, he tapus them; to monopolize trade with a foreign ship for himself, he declares it tapu; to quarantine a European trader he is discontent with, he tapus. Its prohibition then resembles the old “veto” of kings.

When an object is tapu, no one may touch it with impunity. When a native is subject to this prohibition, he may be forbidden from touching certain foods for a period of time. If he is rich, he may be relieved of this severe diet by having his slaves feed him the foods he must not touch with his hands. If he is poor, he is reduced to picking up his food with his mouth, and the tapu reduces him to the status of an animal.

This singular custom directs and controls the smallest actions of the Māori. It is an incessant intervention of the divine in daily life. It is the law of the Māori. The frequent application of the tapu is the indisputable and undisputed native code.

For the captives imprisoned in the Ware Atua, it was an arbitrary tapu which had saved them from the fury of the tribe. Some of the natives, Kai-Kúmu’s friends and partisans, had suddenly stopped at the voice of their chief and had protected the prisoners.

Glenarvan was not under any illusion as to what was going to happen to him. His death alone could pay for the killing of a chief, and death among savage peoples only comes at the end of a long ordeal. Glenarvan expected that he would have to atone for the legitimate indignation which had motivated his action, but he hoped that Kai-Kúmu’s anger would only strike him.

The night passed anxiously for Glenarvan and his companions. Who could picture their agony or measure their suffering? Poor Robert, and the brave Paganel had not reappeared. What was their fate? Were they the first victims sacrificed to the vengeance of the natives? All hope had disappeared, even from the heart of MacNabbs, who did not despair easily. John Mangles felt himself going crazy at the misery and despair of Mary Grant, separated from her brother. Glenarvan was thinking of the terrible request from Lady Helena, who in order to escape torture or slavery, wanted to die at his hand! Would he have the courage to carry out such a horrible act?

“And Mary, do I have the right to kill her?” thought John, his heart breaking.

Escape was obviously impossible. Ten warriors, armed to the teeth, watched at the door of the Ware Atua.

The morning of February 13th arrived. No communication had taken place between the natives and the prisoners forbidden by the tapu. The hut contained some food which the poor inmates barely touched. Misery deadened the pangs of hunger. The day passed without bringing any change, or hope. Doubtless the hour of the dead man’s funeral and the hour of torture were to ring together.

However, if Glenarvan believed that Kai-Kúmu had given up all his ideas of a prisoner exchange, the Major still held a glimmer of hope. “Who knows,” he said, reminding Glenarvan of the strange expression that had crossed Kai-Kúmu’s face on the death of Kára-Téte. “Maybe Kai-Kúmu really does feel obliged to you?”

But, despite MacNabbs’ observation, Glenarvan did not want to hope anymore. Another day passed without any preparations for torture being revealed. There was a reason for this delay.

The Māori believe that the soul lives on in the body of the deceased for three days following death, so the corpse remains unburied for seventy-two hours. This custom of delayed burial was rigorously observed. The pā remained deserted until February 15th. John Mangles, hoisted on Wilson’s shoulders, often observed the outer fortifications. No natives could be seen there. The only ones he saw were the sentinels, relieving each other on guard at the door of the Ware Atua.

But on the third day the huts opened. The savages, men, women, and children, several hundred Māori in all, gathered in the pā, silent and calm.

Kai-Kúmu came out of his hut, and surrounded by the principal chiefs of his tribe, he took his place on a mound raised a few feet in the centre of the fortification. The crowd of natives formed a semicircle a few yards back. The whole assembly kept an absolute silence.

At a sign from Kai-Kúmu, a warrior made his way to the Ware Atua.

“Remember,” Lady Helena said to her husband.

Glenarvan hugged his wife to his heart. At this moment, Mary Grant approached John Mangles.

“Lord and Lady Glenarvan,” she said, “will think that if a woman can die from her husband’s hand to escape a shameful existence, a fiancée can die from her fiancé’s hand as well, to escape in her turn. John, you can tell me, in this final moment, have I not long been your betrothed in the secret of your heart? Can I count on you, dear John, like Lady Helena counts on Lord Glenarvan?”

“Mary!” cried the distraught young captain. “Oh! Dear Mary—”

He could not finish. The mat was raised, and the captives were dragged toward Kai-Kúmu. The two women were resigned to their fate. The men concealed their anxieties in a superhuman calm.

They arrived in front of the Māori chief. He did not delay passing his judgement.

“You killed Kára-Téte?” he asked Glenarvan.

“I killed him,” replied the Lord.

“Tomorrow, you will die at sunrise.”

“Only me?” asked Glenarvan, whose heart beat violently.

“Ah! If only the life of our Tohonga was not more precious than yours!” exclaimed Kai-Kúmu, whose eyes expressed a fierce regret.

There was agitation among the natives. Glenarvan glanced quickly around. The crowd parted, and a warrior appeared, dripping with sweat, panting with fatigue.

Kai-Kúmu, as soon as he saw him, spoke to him in English, with the evident intention of being understood by the captives “You come from the camp of the Pākehās?”

“Yes,” said the Māori.

“You saw the prisoner, our Tohonga?”

“I saw him.”

“He is alive?”

“He is dead! The English shot him!”

It was all over for Glenarvan and his companions.

“All!” cried Kai-Kúmu. “You will all die tomorrow at dawn!”

Thus, these poor souls would all suffer a common fate. Lady Helena and Mary Grant looked up at the sky with sublime thanks.

The captives were not taken back to the Ware Atua. They were to attend Kára-Téte’s funeral and the bloody ceremonies that would accompany it. A troop of natives led them a few steps to the foot of a huge koudi pine tree. Their guards remained, keeping watch over them. The rest of the Māori tribe, absorbed in their official grief, seemed to have forgotten them.

Three days had passed since the death of Kára-Téte. The soul of the deceased warrior had finally abandoned his mortal remains. The ceremony began.

The body was brought to a small knoll in the middle of the pā. He was dressed in lavish garments and wrapped in a beautiful mat of Phormium. His head, decorated with feathers, wore a crown of green leaves. His face, arms, and chest had been rubbed with oil, and showed no sign of decay.

The family and friends arrived at the foot of the hillock, and as one, as if some conductor was beating the measure of the funeral song, an immense concert of tears, moans, and sobs rose in the air. They were crying for the deceased with a plaintive, doleful rhythm. His kinsmen beat their heads; his kinswomen tore at their faces with their nails. They were more prodigal with their blood, than with tears.

These pitiful women conscientiously performed this savage duty, but these demonstrations were not enough to appease the soul of the deceased, whose wrath would undoubtedly have struck the survivors of his tribe. His warriors, unable to return him to life, wanted him to have no regrets of earthly existence in the other world. Kára-Téte’s wife was not to abandon her husband in the grave. The poor woman would have refused to survive him. This was her duty, in accord with their custom, and examples of such sacrifices are common in the history of New Zealand.

The woman appeared. She was still young. Her disordered hair floated around her shoulders. Her sobs and cries rose to the sky: incoherent words, regrets, broken phrases in which she celebrated the virtues of the dead, interrupted by moans. She lay at the foot of the knoll, beating the ground with her head in a supreme paroxysm of sorrow.

Kai-Kúmu approached her. Suddenly the unfortunate victim rose; but a violent blow of the mere, a formidable club, whirling in the chief’s hand, threw her to the ground. She fell as if thunderstruck.

A terrible cry arose. A hundred men threatened the captives, terrified by this horrible spectacle, but no one moved because the funeral ceremony was not finished.

Kára-Téte’s wife had joined her husband in death. The two bodies remained lying close to each other. But for eternal life, it was not enough for the deceased to just have his faithful wife. Who would serve them in the presence of Nui Atua, if their slaves did not follow them from this world to the next?

Six wretches were brought before the corpses of their masters. They were servants whom the pitiless laws of war had reduced to slavery. During the chief’s life, they had suffered the harshest privations, suffered a thousand mistreatments, scarcely fed, constantly used as beasts of burden, and now, according to Māori belief, they were going to continue their slavery for all eternity.

These unfortunate people were resigned to their fate. They were not surprised by this long-awaited sacrifice. Their hands, free from all restraint, testified that they would not defend themselves.

Their deaths were quick. They were spared from long suffering. Torture was reserved for the authors of the murder, who, grouped twenty paces away, averted their eyes from this dreadful spectacle, the horror of which was about to increase.

Six blows from a mere, carried out by the hands of six strong warriors, laid the victims on the ground in the middle of a pool of blood.

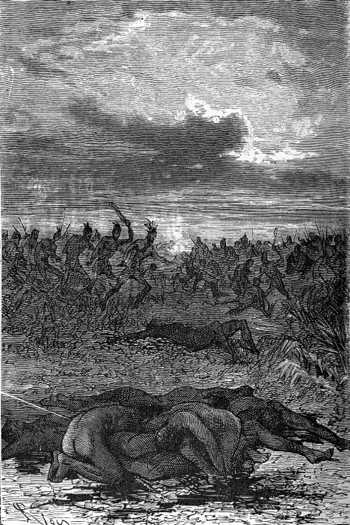

This was the signal to begin a terrible scene of cannibalism

This was the signal to begin a terrible scene of cannibalism.

The body of a slave is not protected by the tapu like the body of the master. It belongs to the tribe. It is the small change thrown to mourners. Also, the sacrifice to be consumed. The whole group of natives, chiefs, warriors, old men, women, and children, without distinction of age or sex, were seized with a bestial fury. They rushed upon the lifeless remains of the victims. In less time than a quick pen could trace it, the bodies, still warm, were torn apart, divided, cut up, not into slices, but into slivers. Of the two hundred Māori present at the sacrifice, each had his share of human flesh. They wrestled, struggled, and competed for the slightest scraps. Drops of hot blood spattered these monstrous revellers, and all this disgusting horde swarmed in a red rain. It was the madness and fury of fierce tigers on their prey. It was like a circus in which the gladiators devoured the wild beasts.

Twenty fires were lit around the pā, and the smell of burnt meat filled the air. Without the dreadful tumult of this feast, without the cries still escaping from the throats engorged with flesh, the prisoners would have heard the bones of the victims cracking between the teeth of the cannibals.

Glenarvan and his companions, breathless, tried to hide this abominable scene from the eyes of the two poor women. They understood then what torture awaited them the next day at sunrise, and, without doubt, what cruel tortures would proceed such a death. They were struck dumb with horror.

The funeral dances began. Strong liqueurs, distilled from the Piper excelsum, true spirit of pepper, intoxicated the savages. They seemed completely inhuman. Would they, forgetting the tapu of the chief, turn in their delirium on the prisoners, who were already terrified by this horrible scene? But Kai-Kúmu had kept his wits in the midst of the general drunkenness. He let this orgy of blood play out for an hour. After peaking in intensity, it faded away again, and the last act of the funeral took place with the usual ceremony.

The corpses of Kára-Téte and his wife were raised, their limbs bent and gathered against their bellies, according to the custom of the Māori. It was now time to bury them, not permanently, but until the earth, having devoured the flesh, left nothing but bones.

The location of the Údu pá, that is to say, the tomb, was chosen outside the fortification, at the top of a small mountain called Maunganamu situated on the east bank of the lake, about two miles away.

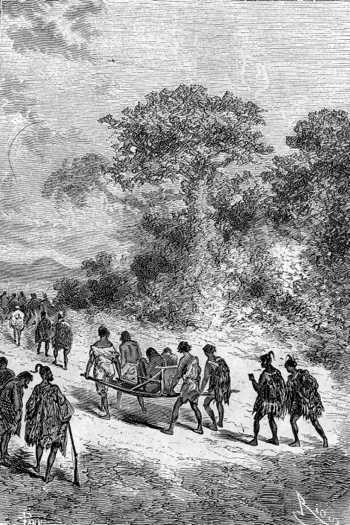

The bodies were brought to the foot of the mound

The bodies were to be transported there, carried on primitive palanquins, little more than stretchers. The corpses were placed on them, folded on themselves in a seated position, rather than lying down, and held that way in their clothes by a circle of lianas. Four warriors lifted the palanquins to their shoulders, and the whole tribe, resuming their funeral anthem, followed them in procession to the burial site.

The captives, still guarded, watched the procession leave the inner enclosure of the pā. The songs and the cries faded away.

For about half an hour this funeral procession remained out of sight in the depths of the valley. Then they saw it again, snaking up the paths of the mountain. The wavy movement of this long, sinuous column in the distance was an uncanny sight.

The tribe stopped at the top of Maunganamu, eight hundred feet above the lake, at the place prepared for the burial of Kára-Téte. A simple Māori would only have had a hole and a pile of stones. But for a powerful and feared chief, destined undoubtedly for deification, his tribe reserved a tomb worthy of his exploits.

The Údu pá was surrounded by palisades, and posts adorned with ocher-reddened figures stood near the grave where the bodies were to rest. The family had not forgotten that the Wairua, the spirit of the dead, feeds on material substances, as the body does during this perishable life. This is why food was left in the compound, as well as the weapons and clothing of the deceased.

Nothing was wanting in the comfort of the tomb. The two spouses were placed next to each other, then covered with earth and grass, after another series of lamentations.

Then the procession silently descended the mountain, and now no one could climb Maunganamu on pain of death, because it was tapu, like Tongariro, where the remains of a chief crushed by an earthquake in 1846 rested.

1. The title of ariki doesn’t have any special religious significance. It simply means “persons of the highest rank and seniority” — DAS