Glenarvan first, then Lady Helena, slid along the rope

As the sun disappeared beyond Lake Taupo, behind the peaks of Tuhahua and Puketapu, the captives were taken back to their prison. They were not to leave it again before the the first light of the day illuminated the peaks of the Huiarau Range.1

They had one night left to prepare to die. Despite their despondency, despite the horror they felt, they took their meal together.

“We will need all of our strength, to look death in the face,” said Glenarvan. “We must show these barbarians that Europeans know how to die.”

When the meal was over, Lady Helena recited the evening prayer aloud. All her companions, bareheaded, joined in it.

Where is the man who does not think of God before his death?

This duty completed, the prisoners embraced.

Mary Grant and Helena retired to a corner of the hut, and lay on a mat. Sleep, which suspends all evils, soon dwelt on their eyelids. They fell asleep in each other’s arms, overcome by exhaustion and long insomnia. Glenarvan took his friends aside.

“My dear companions, our lives, and those of these poor women are with God,” he said. “If it is Heaven’s will that we die tomorrow, I am sure we will die as people of courage, as Christians, ready to appear without fear before the supreme judge. God, who sees the depths of souls, knows that we pursue a noble goal. If death is waiting for us instead of success, it is because God wills it. Hard as it is, I will not murmur against him. But death here is not death only, it is torture, it is infamy, perhaps, and as for the two women…”

Glenarvan’s voice, tightly controlled until then, faltered. He paused to regain his composure. Then, after a moment of silence, he went on.

“John,” he said to the young captain, “you promised Mary what I promised Lady Helena. What have you resolved?”

“I think I have the right before God to fulfill my promise,” said John Mangles.

“Yes, John! But we are without weapons!”

“Here is one,” said John, raising a dagger. “I tore it out of Kára-Téte’s hands, when that savage fell at your feet. My Lord, whichever of us that survives the other will fulfill the wish of Lady Helena and Mary Grant.”

A profound silence reigned in the hut after these words. Finally, the Major interrupted it. “My friends, this can only be done as a last resort. I do not support that which is irrevocable.”

“I did not speak for us,” replied Glenarvan. “Whatever it is, we will brave death! Ah! If we were alone, twenty times already I would have shouted to you ‘My friends, let’s try an escape! Let’s attack these wretches!’ But Helena! Mary! …”

John lifted the mat, and counted twenty-five natives who were watching at the door of the Ware Atua. A great fire had been lit and cast a sinister light on the rugged terrain of the pā. Some of these savages were lying around the fire. Others, standing motionless, stood out strongly against the light of the flames. But all of them cast frequent glances on the hut entrusted to their charge.

It is said that between a jailer who watches and a prisoner who wants to flee, the odds are for the prisoner. The interest of one is greater than the interest of the other. One can forget that he is guarding, the other can not forget that he is guarded. The captive is more likely to flee than his guardian to prevent his escape.

But here, hatred and vengeance kept watch over the captives, not an indifferent jailer. If the prisoners had not been bound, it was because bonds were useless, since twenty-five men were watching over the only way out of the Ware Atua.

This hut, backed against the sheer wall at the rear of the fortress, was accessible only by a narrow tongue of land which connected its front to the plateau of the pā. Its other sides fell away in steep slopes and overlooked an abyss a hundred feet deep. Descent of that cliff was impossible. Nor would there be any way to escape from the bottom of the battlements. The only way out was the entrance of the Ware Atua, and the Māori guarded that tongue of land that united it to the pā like a drawbridge. Any escape was impossible, and Glenarvan, after having probed the walls of his prison twenty times, was obliged to recognize it.

The anxious hours of the night were passing. Pitch blackness covered the mountain. Neither moon nor stars disturbed the deep darkness. A few gusts of wind whirled around the flanks of the pā. The posts of the hut groaned. The natives’ hearth flared up at this passing wind, and the gleams of firelight flickered through the Ware Atua, illuminating the prisoners for a moment: these poor people who were absorbed in their final thoughts. A deathly silence reigned in the hut.

It must have been about four o’clock in the morning, when the Major’s attention was aroused by a slight noise which seemed to be coming from behind the posts at the rear of the hut: the wall backing on the massif. MacNabbs at first ignored this noise, but as it continued, he listened more closely; then, intrigued by its persistence, he pressed his ear against the ground to hear it better. It seemed to him that the scratching was someone digging outside.

When he was certain of what he’d heard, the Major slipped near Glenarvan and John Mangles, tore them from their painful thoughts, and led them to the back of the hut.

“Listen,” he said in a low voice, beckoning them to bend down.

The scratches were becoming more pronounced; you could hear small stones grinding against a hard surface as they were rolled away.

“Some beast in its burrow?” said John Mangles.

Glenarvan slapped his forehead. “Who knows. What if it’s a man?”

“Man or animal,” said the Major, “We will soon find out!”

Wilson and Olbinett joined their companions, and they all began to dig by the wall, John with his dagger, the others with stones torn from the ground or with their fingernails. Mulrady, lying on the ground, watched the company of guarding natives through the gap at the bottom of the mat covering the door.

These savages, motionless around the fire, suspected nothing of what was happening twenty paces from them.

The ground was made up of loose, friable soil that covered the siliceous tuff. Despite the lack of tools, the hole grew quickly. Soon it was evident that a man or men, clinging to the flanks of the pā, was cutting a passage in its outer wall. What could be their goal? Did they know of the existence of the prisoners, or did some other venture explain the work that was being undertaken?

The captives redoubled their efforts. Their torn fingers were bleeding, but they kept digging. After half an hour of work, the hole they’d dug had reached a depth of half a metre. They could tell from the louder sounds that only a thin layer of earth prevented immediate communication.

A few more minutes passed, and suddenly the Major withdrew his hand, cut by a sharp blade. He bit back the cry that tried to escape his lips.

John Mangles, digging with the blade of his dagger, avoided the knife that was protruding above the ground, but he seized the hand that held it.

It was a woman’s, or a child’s hand — a European hand!

Not a word had been uttered, by either side. It was obvious that both sides wanted to keep quiet.

“Is it Robert?” murmured Glenarvan.

But, as low as he had pronounced this name, Mary Grant, who had been awakened by the movements that were taking place in the hut, slipped beside Glenarvan, and seizing that hand all spotted with earth, she covered it with kisses.

“It is! It is!” said the girl, who could not have been mistaken, “It’s you, my Robert!”

“Yes, little sister,” replied Robert, “I am here to save you all! But, be quite!”

“Brave child!” said Glenarvan.

“Watch the savages outside,” said Robert.

Mulrady, momentarily distracted by the appearance of the child, resumed his observation post. “All is well,” he said. “There are only four warriors keeping watch. The others are asleep.”

“Courage!” said Wilson.

In an instant, the hole was enlarged, and Robert passed from his sister’s arms into Lady Helena’s. A long Phormium rope was coiled around his body.

“My child, my child,” murmured the young woman. “The savages didn’t kill you!”

“No, Madame,” said Robert. “I do not know how, but during the confusion, I was able to hide myself from their eyes. I crossed the enclosure, and I remained hidden behind shrubs for two days. I slept at night; I wanted to see you again. While the whole tribe was busy with the funeral of the chief, I came to scout the side of the fortress where the prison stands, and I saw that I could reach you. I stole that knife and rope from a deserted hut. Tufts of grass, and branches of shrubs served me as a ladder. I was lucky to find a sort of cave dug in the massif beneath where this hut rests. I had only a few feet to dig in soft ground, and here I am.”

Twenty silent kisses were the only answer Robert could get.

“Let’s go!” he said in a determined tone.

“Is Paganel down below?” asked Glenarvan.

“Monsieur Paganel?” asked the child, surprised at the question.

“Yes, is he waiting for us?”

“No, My Lord. What? Monsieur Paganel is not here?”

“He’s not here, Robert,” said Mary Grant.

“What? Didn’t you see him?” asked Glenarvan. “You didn’t meet in the confusion? You didn’t escape together?”

“No, My Lord,” said Robert, aghast to learn of the disappearance of his friend Paganel.

“Let’s go,” said the Major. “There is not a minute to lose. Wherever Paganel is, he can not be worse off than we are. Let’s go!”

Indeed, moments were precious. They had to flee. The escape did not present great difficulties, except for an almost perpendicular wall outside the tunnel, but that was only twenty feet. Afterward, the slope offered a gentle descent to the bottom of the mountain. From there, the captives could quickly reach the lower valleys while the Māori, if they came to notice their flight, would be forced to make a very long detour to reach them, since they were unaware of the existence of this tunnel dug between the Ware Atua and the outer slope.

The escape began. Every precaution was taken to make it succeed. The captives passed one by one through the narrow tunnel and found themselves in the cave. John Mangles, before leaving the hut, tidied up the debris from their hole and slipped in his turn through the opening, pulling the mats from the hut over the opening behind him. The tunnel was therefore entirely concealed.

It was now necessary to descend the perpendicular wall to the slope, and this descent would have been impossible had Robert not brought the Phormium rope.

They unrolled it, fixed it to a projection of rock, and threw it out.

John Mangles, before letting his friends hang on these Phormium filaments, twisted together into a rope, felt them. They did not appear very strong to him. It was necessary not to risk themselves rashly, for a fall could be fatal.

“This rope can only bear the weight of two people,” he said, “so, proceed accordingly. Let Lord and Lady Glenarvan go first. When they arrive at the embankment, three tugs on the rope will give us the signal to follow them.”

“I’ll go first,” said Robert. “I found a deep hole at the bottom of the embankment where the first ones down can hide to wait for the others.”

“Go, my child,” said Glenarvan, shaking the boy’s hand.

Robert disappeared through the cave opening. A minute later, three tugs of the rope indicated that he had successfully reached the bottom.

Glenarvan and Lady Helena immediately ventured out of the cave. The darkness was still deep, but a few grey tints were already shading the peaks that rose in the east.

The brisk morning cold revived the young woman. She felt stronger and began her perilous escape.

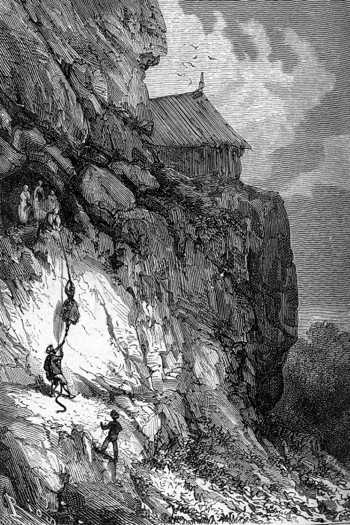

Glenarvan first, then Lady Helena, slid along the rope

Glenarvan first, then Lady Helena, slid along the rope to where the perpendicular wall met the top of the embankment. Then Glenarvan, preceding his wife and supporting her, began to descend backwards. He sought for tufts of grass and shrubs to offer him a foothold; he found them first, and then guided the feet of Lady Helena. A few birds, awakened suddenly, flew away with little cries, and the fugitives shuddered when a stone, detached from its hollow, rolled noisily down to the bottom of the mountain.

They had descended half of the slope, when they heard a voice from the opening of the cave.

“Stop!” whispered John Mangles.

Glenarvan, clinging with one hand to a clump of Tetragonia, and holding his wife with the other, waited, barely breathing.

Wilson had heard some noise outside the Ware Atua. He had returned to the hut, and, raising the mat, he was observing the Māori. At a signal from him, John had stopped Glenarvan.

One of the warriors, aroused by some strange sound, had gotten up and approached the Ware Atua. Standing a stone’s throw from the hut, he listened with his head cocked. He remained in this attitude for a minute that seemed like an hour, listening and watching intently. Then, shaking his head like a man who misapprehended himself, he returned to his companions, took an armful of dead wood, and threw it into the half-extinguished fire, reviving its flames. His face, brightly lit, betrayed no more preoccupation, and after observing the first glimmers of dawn lightening the horizon, he settled down by the fire to warm his cold limbs.

“Everything is fine,” Wilson said.

John motioned Glenarvan to resume his descent. Glenarvan slid gently down the slope; soon he and Lady Helena stepped onto the narrow path where Robert was waiting for them.

The rope was shaken three times, and in turn John Mangles, preceding Mary Grant, followed the perilous way. When they reached the bottom they joined Lord and Lady Glenarvan in the depression found by Robert.

Five minutes later, all the fugitives, so fortuitously escaped from the Ware Atua, left their provisional retreat, and fleeing the inhabited banks of the lake, they plunged by narrow paths, deeper into the mountains.

They moved quickly, trying to avoid any place where some lookout might see them. They did not speak, they slid like shadows through the shrubs. Where were they going? They didn’t know, but they were free.

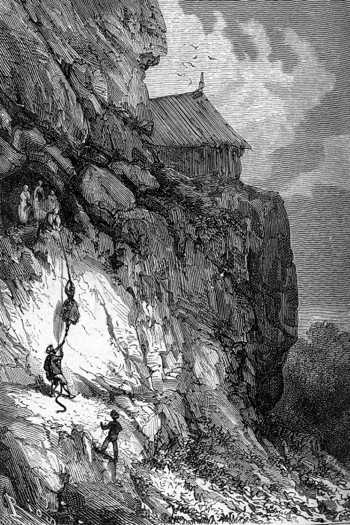

The day began to dawn at about five o’clock

The day began to dawn at about five o’clock. Shades of blue marbled the high clouds. The misty peaks emerged from the morning fog. The day star would soon appear, and this sun, instead of signalling the beginning of the torture, would, on the contrary, announce the flight of the condemned.

It was necessary to put as much distance as possible between themselves and the natives before their escape was discovered. But they could not move quickly over the steep trails. Lady Helena climbed the slopes, supported, not to say carried, by Glenarvan, and Mary Grant leaned on the arm of John Mangles. Robert, happy, triumphant, his heart full of joy at his success, led the march. The two sailors brought up the rear.

Another half hour, and the sun would emerge from the mists of the horizon.

For half an hour, the fugitives went on as chance led them. Paganel was not there to guide them. They were all concerned about Paganel; his absence cast a dark shadow over their happiness. They headed east, as nearly as possible, and advanced toward a magnificent dawn. Soon they had reached a height of five hundred feet above Lake Taupo, and the morning chill, increased by this altitude, stung them sharply. Indistinct forms of hills and mountains stood one above the other; but Glenarvan only wanted to get lost. Later, he would look for a way out of this mountainous labyrinth.

At last the sun appeared, and sent its first rays to meet the fugitives.

Suddenly a terrible scream, made up of a hundred cries, burst into the air. It rose from the pā. Glenarvan didn’t know its exact position. A thick curtain of mists stretching under his feet prevented him from seeing into the low valleys.

But the fugitives could not doubt that their escape was discovered. Would they escape the pursuit of the natives? Had they been seen? Would their tracks betray them?

The lower fog rose, momentarily enveloping them with a damp cloud before it cleared, and they saw, three hundred feet below them, the frenetic mass of natives.

They saw, but they had also been seen. A hue and cry broke out, and the whole tribe, after tying in vain to climb the rock walls by the Ware Atua, rushed out of the pā, and darted by the shortest paths in pursuit of the prisoners who were fleeing their vengeance.

1. Verne has “Wahiti Ranges” here, but I can find no reference to any mountain range with that name anywhere in New Zealand. I have substituted “Huiarau” which is the name of the mountains east of Lake Taupo (though they are quite a bit farther east than the mountains Verne describes.)