“Sit down please, my dear Lord”

The summit of the mountain was still a hundred feet above them. The fugitives hoped to disappear from the Māori’s sight on the opposite side. They hoped that some passable ridge would allow them to reach the jumble of neighbouring peaks, an intricate network of mountains, which poor Paganel would have doubtless, if he had been with them, sorted out the complications.

They hurried up the mountain, pursued by the shouts which were getting closer and closer. The pursuing horde arrived at the foot of the mountain.

“Courage, my friends! Courage!” shouted Glenarvan, encouraging his companions with voice and gesture.

In less than five minutes they reached the summit. There, they paused to judge the situation and to choose a direction which might evade the Māori.

From this height, their gaze took in all of Lake Taupo, which stretched westward in its picturesque setting of mountains; to the northwest, the peaks of Pirongia; to the south, the fiery crater of Tongariro. But to the east, the eye stumbled against the barrier of peaks and ridges which formed the Huiarau Ranges, part of the chain of ranges that crosses the whole northern island from the East Cape to Cook Strait. They had to descend the opposite side and enter its narrow gorges, perhaps without exit.

Glenarvan glanced anxiously around him; the fog had melted in the rays of the sun, his gaze penetrated into the smallest hollows of the ground. No Māori movement could escape his sight.

The natives were not five hundred feet from him when they reached the plateau on which the solitary cone rested.

Glenarvan could not prolong this halt for a moment. Exhausted or not, they had to flee, or they would be surrounded.

“Let’s go!” he exclaimed, “let’s go before we’re cut off!”

But as the poor women were rising by a desperate effort, MacNabbs stopped them.

“It’s unnecessary, Glenarvan,” he said. “See.”

And all, indeed, saw the inexplicable change that had occurred in the onrush of the Māori.

Their pursuit had suddenly stopped. The assault on the mountain had ceased as by an peremptory command. The band of natives had ceased its momentum, and had stopped like the waves of the sea breaking against an immovable rock.

All these savages, hungry for blood, now ranged around the foot of the mountain, howling, gesticulating, waving their guns and axes, but they did not advance one foot up the mountain. Their dogs, also rooted on the spot, barked furiously.

What was going on? What invisible power held the natives? The fugitives looked down without understanding, fearing that the charm which chained the tribe of Kai-Kúmu would break.

Suddenly, John Mangles uttered a cry that made his companions turn around. He pointed toward a small fortress raised at the top of the cone.

“It’s the tomb of Chief Kára-Téte!” exclaimed Robert.

“Are you sure, Robert?” asked Glenarvan.

“Yes, My Lord, it is the tomb! I recognize it.”

Robert was correct. Fifty feet above, at the very top of the mountain, freshly painted posts formed a small, palisaded enclosure. Glenarvan too, now recognized the tomb of the Māori chief. The fortunes of their escape had brought them to the very top of Maunganamu.

The Lord, followed by his companions, climbed the last slopes of the cone to the very foot of the tomb. A wide opening covered with mats gave access to it. Glenarvan was about to enter the interior of the Údu pá when he suddenly stepped back sharply.

“A savage!” he said.

“A savage in this tomb?” asked the Major.

“Yes, MacNabbs.”

“What does it matter? Go in.”

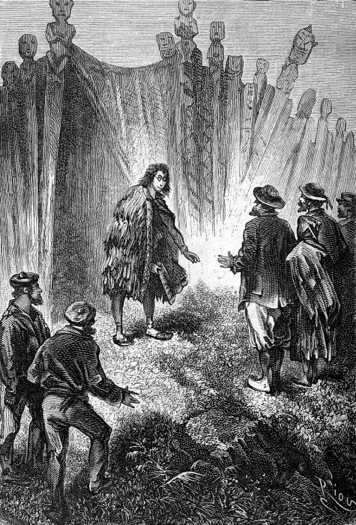

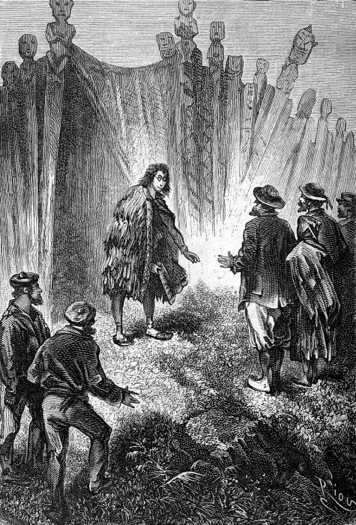

Glenarvan, the Major, Robert, and John Mangles entered the compound. There was a Māori there, wearing a large Phormium cloak. The gloom of the Údu pá hid his features. He seemed very quiet, and was eating his breakfast with the utmost casualness. Glenarvan was about to speak to him, when the native, very politely, and with a kind voice, spoke to him in good English.

“Sit down please, my dear Lord”

“Sit down please, my dear Lord, breakfast is waiting for you.”

It was Paganel. On hearing his voice, everyone rushed into the Údu pá to exchange joyous hugs with the excellent geographer. Paganel was found! They were all saved! They all wanted to question him. They wanted to know how and why he was at the top of Maunganamu, but Glenarvan stopped this untimely curiosity.

“The savages!” he said.

“The savages,” Paganel shrugged. “I supremely despise those people!”

“But can’t they…?”

“Them? The fools! Come see them!”

They all followed Paganel out of the Údu pá. The Māori hadn’t moved, surrounding the foot of the cone, and uttering frightful shouts.

“Shout! Yell! Wear yourselves out, you stupid creatures!” cried Paganel. “I challenge you to climb this mountain!”

“Why?” asked Glenarvan.

“Because the chief is buried here; because his tomb protects us; because the mountain is tapu!”

“Tapu?”

“Yes, my friends! And that is why I took refuge here, as many wretches in the middle ages took sanctuary in a church.”

“God is on our side!” exclaimed Lady Helena, raising her hands to the heavens.

Paganel was correct. The mount was tapu, and because of its consecration, the superstitious savages would not invade it.

This wasn’t an escape for the fugitives, but it gave them a respite that they hoped would benefit them. Glenarvan, overcome by indescribable emotion, did not say a word, and the Major shook his head with a truly satisfied air.

“And now, my friends,” said Paganel, “if these brutes believe they can wait us out, they are mistaken. We will be out of the reach of these rascals within two days.”

“We will escape!” said Glenarvan. “But how?”

“I do not know,” said Paganel, “but we will think of something.”

Everyone wanted to know about the geographer’s adventures. It was somewhat bizarre, but for such a loquacious man, he was showing singular restraint in describing what had befallen him. It was necessary to drag his account from his lips in bits and pieces. He, who normally loved to talk so much, replied to many of his friends’ questions with evasions.

“They have changed my Paganel,” thought MacNabbs.

In fact, the appearance of the worthy scholar had changed. He wrapped himself tightly in his vast Phormium shawl, and seemed to avoid too inquisitive looks. His embarrassed manner, when someone asked about him, escaped no one, but, by discretion, no one seemed to notice them. Moreover, when Paganel was no longer the subject, he resumed his usual playfulness.

As for his recollections, here is what he thought fit to tell his companions when they were all seated near him, at the foot of the Údu pá’s palisade:

After the death of Kára-Téte, Paganel, like Robert, took advantage of the natives’ turmoil, and escaped the enclosure of the pā. But, less fortunate than the young Grant, he stumbled into another Māori encampment. This camp was commanded by a handsome, intelligent-looking chief, evidently superior to all the warriors of his tribe. This leader spoke good English, and welcomed the geographer with the nose to nose hongi greeting in which two people exchange the breath of life.

At first, Paganel wondered whether he should consider himself a prisoner or not. But he soon found that he could not take a step without being kindly accompanied by the chief, so he knew what to expect in this respect.

This chief, named “Híhi,” which means “sunbeam,” was not a wicked man. The geographer’s spectacles and telescope seemed to give him a high regard of Paganel, and he attached it particularly to himself, not only by granting him his protection, but also by strong Phormium chords. Especially at night.

This situation lasted three long days. They asked if he was well or poorly treated, to which Paganel would only say “Yes and no,” without further explanation. In short, he was a prisoner, and, except for the prospect of immediate execution, his condition seemed to him hardly more enviable than that of his unfortunate friends.

Fortunately, one night he managed to gnaw through his ropes and escape. He had witnessed the burial of the chief from afar. He knew that he had been buried at the top of Maunganamu, and that this had made the mountain tapu. It was there that he resolved to take refuge, not wishing to leave the area where his companions were detained. He succeeded in his perilous escape. He arrived at the tomb of Kára-Téte last night, and waited there, “while recovering strength,” hoping that Heaven might, through some chance, deliver his friends.

That was Paganel’s story. Did he purposely omit certain incidents from his stay with the natives? More than once, his evident embarrassment made everyone believe so. Be that as it may, he received unanimous congratulations, and with his story completed, they returned their concern to the present.

Their situation was extremely dire. The natives, if they did not venture to climb up Maunganamu, counted on hunger and thirst to drive their prisoners down. It was a matter of time, and the savages have long patience.

Glenarvan had no illusions about the difficulties of his position, but he resolved to wait for favourable circumstances, or to make them, if necessary.

First, Glenarvan wished to carefully scout his improvised fortress of Maunganamu — not to defend it, for attack was not to be feared, but to find a way to leave it. He, the Major, John, Robert, and Paganel made a survey of the mountain. They observed the directions of the paths, their ends, their slopes. A ridge, one mile long, which united Maunganamu to the Huiarau Range, descended close to the plain. Its spine, narrow and capriciously contoured, presented the only feasible route by which an escape might be made. If the fugitives crossed it unnoticed in the night, perhaps they would be able to get into the deep valleys of the Ranges and evade the Māori warriors.

But this route offered more than one danger. At its lowest point, it passed within gunshot range of the Māori. Natives posted on the lower slopes could set up a crossfire there, and stretch a net of lead across the ridge that no one could pass with impunity.

Glenarvan and his friends, having ventured onto the dangerous part of the ridge, were saluted with a hail of lead which fell short of them. A few bits of smouldering wadding, carried by the wind, did reach them. They were made of printed paper which Paganel picked up out of pure curiosity and deciphered with some difficulty.

“Ha!” he said. “Do you know, my friends, what these animals stuff their rifles with?”

“No, Paganel,” said Glenarvan.

“With slips of the Bible! If this is the use they make of sacred verses, I pity the missionaries! They will have trouble founding Māori libraries.”

“And what passage of the holy books have these natives fired at us?” asked Glenarvan.

“A word from Almighty God,” said John Mangles, who had just read the paper singed by the explosion. “This word tells us to hope in Him,” added the captain, with the unshakable conviction of his Scottish faith.

“Read it, John,” said Glenarvan.

And John read this verse that survived the explosion of the powder. “Psalm 91:14. ‘Because he hath set his love upon me, therefore will I deliver him.’”

“My friends, we must deliver these words of hope to our brave and dear companions,” said Glenarvan. “This is something that will revive their hearts.”

Glenarvan and his companions returned up the steep slopes of the cone to the tomb they wished to further examine.

On the way, they were astonished, at times, to feel a slight vibration in the ground. It was not a shaking, but more like the continuous vibration experienced by the walls of a boiler. Vapour arising from the action of the subterranean fires was evidently stored under great pressure within the envelope of the mountain.

This could not particularly amaze people who had just passed between the hot springs of the Waikato. They knew that this central region of Te Ika-a-Māui is essentially volcanic. It is a veritable sieve whose fabric lets the earth’s vapours escape through boiling springs and solfataras.

Paganel, who had already observed it, called the attention of his friends to the volcanic nature of the mountain. Maunganamu was just one of the many cones that bristle in the central plateau of the island. It was a volcano in the making. The slightest mechanical action could create a crater in its walls made of a siliceous and whitish tuff.

“Indeed,” said Glenarvan, “but we are no more in danger here than with the Duncan’s boiler. The crust of the earth makes a solid plate!”

“True,” said the Major. “But a boiler, good as it may be, always breaks down after a long service.”

“MacNabbs,” said Paganel, “I do not wish to stay on this cone. Let Heaven show me a passable road, and I will leave it at once.”

“Ah! Why can’t this Maunganamu take us himself,” said John Mangles. “So much mechanical power is contained in its flanks! There may be, under our feet, the strength of several millions of horses, sterile and lost! Our Duncan could carry us to the ends of the world with a thousandth of this power!”

This memory of the Duncan, evoked by John Mangles, brought the saddest thoughts back to Glenarvan’s mind. As desperate as his own situation was, he often forgot it, to mourn the fate of his crew.

He was still thinking of them when he returned to his companions in misfortune at the top of Maunganamu.

Lady Helena came to him as soon as she saw him. “My dear Edward, did you reconnoiter our position? Should we hope or fear?”

“Hope, my dear Helena,” said Glenarvan. “The natives will never climb the mountain, and in time we will form an escape plan.”

“Besides, Madame,” said John Mangles, “God himself recommends for us to hope.”

He handed Lady Helena the page of the Bible, which contained the sacred verse. The young woman and the girl — with their confident souls, their hearts open to all the interventions of Heaven — saw an infallible omen of salvation in these words from the holy book.

“Now, to the Údu pá!” said Paganel, gayly. “This is our fortress, our castle, our dining room, our office! Nobody will bother us! Ladies, allow me to do you the honours of this charming dwelling.”

They followed the amiable Paganel. When the savages saw the fugitives again desecrating this tapu tomb, they fired numerous gunshots and terrible howls arose, each as noisy as the other. But, fortunately, the bullets did not carry as far as the cries, and fell half way, while the shouts were lost in the air.

Lady Helena, Mary Grant, and their companions, quite reassured by seeing that the Māori superstition was even stronger than their anger, entered the funereal monument.

The Údu pá of the Māori chief was a palisade of red painted posts. Symbolic figures, a veritable tattoo on wood, told of the nobility and the deeds of the deceased. Strings of amulets, shells, or cut stones swayed between the poles. Inside, the ground was covered with a carpet of green leaves. In the centre, a slight mound betrayed the freshly dug grave.

The chief’s weapons rested there, his loaded and primed rifles, his spear, and his superb green jade axe, along with a sufficient supply of powder and bullets for the eternal hunts.

“That’s a whole arsenal,” said Paganel, “we’ll make better use of it than the deceased. It’s a good thing that these savages carry their weapons into the other world!”

“Hey! These are English manufactured guns!” said the Major.

“No doubt,” said Glenarvan. “It is a foolish custom to give firearms to the savages that they can then turn against their invaders, and they are right to do so! In any case, these guns can be useful to us!”

“But what will be more useful to us,” said Paganel, “are the food and water destined for Kára-Téte.”

Indeed, the family and friends of the deceased had not been stingy. The supply testified to their esteem for the virtues of the chief. There was enough food to feed ten people for fifteen days, or rather the deceased for eternity. These plant-based foods consisted of ferns, sweet potatoes — indigenous Ipomoea batatas — and potatoes imported into the country long ago by Europeans. Large vases contained the pure water which appears in Māori meals, and a dozen artistically woven baskets contained tablets of an unknown green gum.

The fugitives were therefore provisioned against hunger and thirst for a few days. They had no compunctions against taking their first meal at the expense of the chief.

Glenarvan noted that they had the food they needed, and entrusted it to the care of Mr. Olbinett. The steward, always formal, even in the most serious situations, found the menu of the meal a little thin. Besides, he did not know how to prepare these roots, and he had no fire. But Paganel took matters in hand, and advised him to simply bury the ferns and sweet potatoes in the soil itself.

The temperature of the upper layers was very high, and a thermometer, sunk in this ground, would certainly have indicated a temperature of sixty to sixty-five degrees.1 Olbinett was even very nearly seriously scalded, for as he was digging a hole in which to deposit his roots, a column of steam burst forth, and whistled a fathom up into the air.

The steward fell back

The steward fell back, terrified.

“Shut the tap!” cried the Major, who, with the aid of the two sailors, ran up and filled the hole with pumice debris, while Paganel looked at this phenomenon with a singular air.

“Tiens! Tiens! Hé! Hé! Pourquoi pas?” he murmured.

“Are you hurt?” MacNabbs asked Olbinett.

“No, Mr. MacNabbs,” said the steward, “but I did not expect so much—”

“So many blessings from Heaven!” Paganel exclaimed cheerfully. “After the water and the food of Kára-Téte, the fire of the earth! This mountain is a paradise! I propose to found a colony here, to cultivate it, to settle here for the rest of our days! We will be the Robinsons of Maunganamu! In truth, I search in vain for what we miss on this comfortable cone!”

“Nothing, if it’s solid,” said John Mangles.

“Well! It was not made yesterday,” said Paganel. “It has resisted the force of the interior fires for a long time, and it will hold until well after we leave.”

“Breakfast is served,” announced Mr. Olbinett, as gravely as if he had been performing his duties at Malcolm Castle.

At once the fugitives, seated near the palisade, began one of those meals which for some time Providence had sent them precisely when it was most needed.

There was little choice in what to eat, and opinions were divided on the edible fern root. Some found it sweet and pleasant to the taste, the others bland, perfectly tasteless, and a remarkably tough. The sweet potatoes, cooked in the hot earth, were excellent. The geographer remarked that Kára-Téte was not to be pitied.

Then, hunger sated, Glenarvan proposed that they discuss their escape plan without delay.

“Already!” said Paganel, in a truly pitiful tone. “How are you thinking about leaving this place of delights?”

“But, Monsieur Paganel,” said Lady Helena. “Admitting that we are at Capua, you know that we must not imitate Hannibal!”

“Madame,” replied Paganel, “I will not allow myself to contradict you, and since you wish to discuss it, let us discuss.”

“I think first of all,” said Glenarvan, “that we must attempt an escape before being driven out by hunger. We still have our strength, and we must take advantage of it. Next night, we will try to reach the valleys of the east by crossing the circle of natives under the cover of darkness.”

“Perfect,” replied Paganel, “if the Māori let us pass.”

“What if they stop us?” asked John Mangles.

“Then we will use the great means,” said Paganel.

“So, you have great means?” asked the Major.

“More than I know what to do with!” said Paganel without further explanation.

It only remained to wait for the night to try to cross the line of the natives.

They had not gone away. Their ranks even seemed to have grown with the arrival of the tribe’s stragglers. Burning hearths formed a belt of fires spread around the base of the cone. When darkness invaded the surrounding valleys, Maunganamu appeared to rise out of a vast fire, while its summit was lost in a thick darkness. Six hundred feet below, the agitation, shouts, and murmur of the enemy’s camp could be heard.

At nine o’clock, when it was very dark, Glenarvan and John Mangles resolved to make a reconnaissance, before leading their companions on this dangerous path. They descended quietly for about ten minutes, and mounted the narrow ridge which crossed the native line, fifty feet above the camp.

All was well until then. The Māori, lying near their fires did not seem to see the two fugitives, who took a few more steps. Suddenly, to the left and right of the ridge, a double fusillade broke out.

“Back!” shouted Glenarvan. “These bandits have cat’s eyes and riflemen!”

He and John Mangles immediately ascended the steep slopes of the mountain, and promptly reassured their friends, frightened by the gunfire. Glenarvan’s hat had been shot twice. It was impossible to cross the lengthy ridge between these two ranks of skirmishers.

“I’ll see you in the morning,” said Paganel. “And since we can not deceive the vigilance of these natives, you will allow me to serve them a dish of my own!”

The night was quite cold. Fortunately, Kára-Téte had carried his best night clothes to his grave. The fugitives had no scruples against wrapping themselves in these warm Phormium blankets, and soon, guarded by the native superstition, they slept quietly in the shelter of the palisades, on this lukewarm soil, shivering with interior bubbling.

1. 140° to 150° Fahrenheit — DAS